$\Psi \rightarrow \text{everything}$

Schrodinger Postulate: The wavefunction is found by solving the Schrödinger equation.

$\hat{H}\Psi(x,t) = i \hbar \dot{\Psi}$ or $\hat{H}\Psi = E \Psi$.

Relativitistic quantum mechanics (the Dirac equation) is needed when particles are moving close to the speed of light

Born Postulate: $\left|\Psi(x,t) \right|^2$ is the probability of observing the system at position $x$ at time $t$.¶

$\Psi(x,t)$ is the "square root of reality".

Correspondence Principle: Every observable operator corresponds to a linear Hermitian operator.¶

The analogue of a classical measurement is evaluating the expectation value of a suitable Hermitian operator. The only possible values that can be obtained from a measurement are the eigenvalues of the corresponding Hermitian operator.

We will now elaborate on each of these key postulates. Note that some people list more postulates. There is a some choice in how one groups the information in the postulates together, and I prefer to group the statements about Hermitian operators together.

The wavefunction is sufficient to determine all observable information about a quantum system. This does not mean that all information about a system can be observed. For example, while every classical observable corresponds to a Hermitian operator, it can be impossible to determine the values of multiple classical observables simultaneously.

As is often true, there are subtleties related to this postulate. In practice, we often use a density matrix, rather than a wavefunction, to describe a quantum system. A density matrix is just a mathematical way to capture a mixture of different quantum states, and can be written as, $$ \Gamma(x,t;x',t') = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} p_k \left(\Psi_k(x',t') \right)^*\Psi_k(x,t) $$ The interpretation of a density matrix is that it is a mixture of quantum states, where the probability of observing the quantum state $k$ is $p_k$. It makes sense, therefore, to restrict $p_k$ to satisfy the constraints: $$ 1 = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} p_k \qquad 0 \le p_k \le 1 $$ As with the wavefunction, the normalization of the density matrix is really only a convention. Any bounded (i.e. normalizable) positive semidefinite Hermitian operator can be interpreted as a density matrix. Bounded, positive semidefinite, non-Hermitian operators can be interpreted as transition density matrices, and are the mathematical representation for a change in a quantum state.

The wavefunction (or density matrix) is the central object in quantum mechanics. It is found by solving the Schrödinger equation in its time-independent or time-dependent form. For relativisitic particles, one needs to instead consider the Dirac equation, and for relativisitic particles interacting with light, one needs to consider quantum electrodynamics. If one needs to go beyond this (e.g., to include $\beta$ decay of nuclei), then one needs to extend even further, eventually all the way to the standard model.

For the purposes of this course, the Schrödinger equation is adequate. Relativisitic effects are important in chemistry: it is not uncommon to consider that corrections to the nonrelativistic Schrödinger equation become important for molecules containing elements heavier than Zinc (Z=30) or Krypton (Z=36). However, actinide compounds can, by mathematical trickery, be treated by embellishing the Schrödinger equation in most cases. This means that for the purposes of understanding the structures of molecules and materials, their stability and thermodynamic properties, and the structural and chemical transformations between materials, the (relativistically-corrected) Schrödinger equation is used.

Colloquially, the Born postulate states that the wavefunction is the square root of reality. The wavefunction is a mathematical artifice, and is not directly observable. It's complex square is observable ($|\Psi(x,t)|^2$ indicates the probability of finding the quantum system at the location $x$ at time $t$) and the overlap (interference patterns) between two wavefunctions (e.g., the system's wavefunction and light or another electron) can also be observed.

The first two postulate of quantum mechanics indicate that the wavefunction is the conveyor of all information about a quantum system and how the wavefunction is to be determined. The remaining postulate(s) all indicate that information about a quantum system is deduced from the action of Hermitian operators.

The correspondence principle says that to every classical observable, there exists a Hermitian operator. This Hermitian operator provides the quantum manifestation of that classical observable. In the classical limit (where Planck's constant approaches zero, $h \rightarrow 0$), the quantum mechanical operator and the classical observable coincide. For example, we have used that the quantum mechanical operator for the momentum of a particle moving in one dimension is $$ \hat{p} = -i \hbar \tfrac{d}{dx} $$ There are some caveats associated with this. Some classical observables do not have unique representations in quantum mechanics. For example, in classical mechanics it is sensible to define, and measure, a local kinetic energy, that is, the kinetic energy at of a particle at a given point in space. Because one cannot specify the momentum (or its square) and position of a particle simultaneously, however, one cannot specify the kinetic energy at a point in space in quantum mechanics. So the local kinetic energy is not well-defined in quantum mechanics.

In classical mechanics, all classical observables can be computed from the positions and momenta of the particles in the system. That is, classical observables of an $N$-particle system functions of particles' positions ,$\{\mathbf{r}_k\}$, and momenta, $\{\mathbf{p}_k\}$: $$ f(\mathbf{r}_1,\mathbf{r}_2,\ldots,\mathbf{r}_N;\mathbf{p}_1,\mathbf{p}_2,\dots,\mathbf{p}_N) $$

In quantum mechanics, operators that depend either on the particle's positions or their momenta are clearly defined, but simultaneous observation of both is not. There can be multiple mathematical representations for the quantum-mechanical analogue of a single classical observable, therefore. In practice, such ambiguities do not matter much since the most important observables are those that can be clearly defined. Sometimes, however, chemists like to discuss quantities (like the energy of a single atom or functional group in a molecule, or the interaction energy between two subsystems in a intermolecular complex) which are not defined in quantum mechanics. Such discussions can be useful in practice, but they are contrary to the spirit of quantum mechanics (even though they are deeply entangled with the language of chemistry).

There are also entities that emerge in molecular quantum mechanics that have no classical analogue whatsoever: concepts like electronegativity, oxidation state, and bond order. One should not expect for such quantities, which are intrinsically tied to the properties of electrons and have no classical analogue, to correspond to quantum-mechanical observable or Hermitian operators.

In summary:

Quantum-mechanical observables correspond to Hermitian operators. An operator, $\hat{Q}$ is Hermitian if for any wavefunctions $\psi(x)$ and $\phi(x)$ $$ \int \left( \psi(x) \right)^* \hat{Q} \phi(x) dx = \int \left(\hat{Q} \psi(x) \right)^* \phi(x) dx = \int \left( \hat{Q} \right)^*\left( \psi(x) \right)^* \phi(x) dx $$ This basically means that a Hermitian operator can act either forwards or backwards. This is very useful in practice, since sometimes it is easier to apply $\hat{Q}$ to $\psi(x)$ than to $\phi(x)$.

Note: Quantum-mechanical observables do not need to be Hermitian; it is sufficient for them to be essentially self-adjoint, which is a somewhat weaker concept. While this is not quite a mere mathematical nuance (e.g., the molecular Hamiltonian is essentially self-adjoint), it does not affect the way we use quantum mechanics as a computational tool within chemistry.

Hint: Choose $\Psi(x) = \psi(x) + i \phi(x)$.

Hint: use integration by parts and assume the wavefunction and its derivatives are zero at $\pm \infty$.

In an experimental measurement of a quantum-mechanical observable, the measured value is always one of the eigenvalues of the Hermitian operator.

In an experimental measurement of a quantum-mechanical observable, the measured value is always one of the eigenvalues of the Hermitian operator.

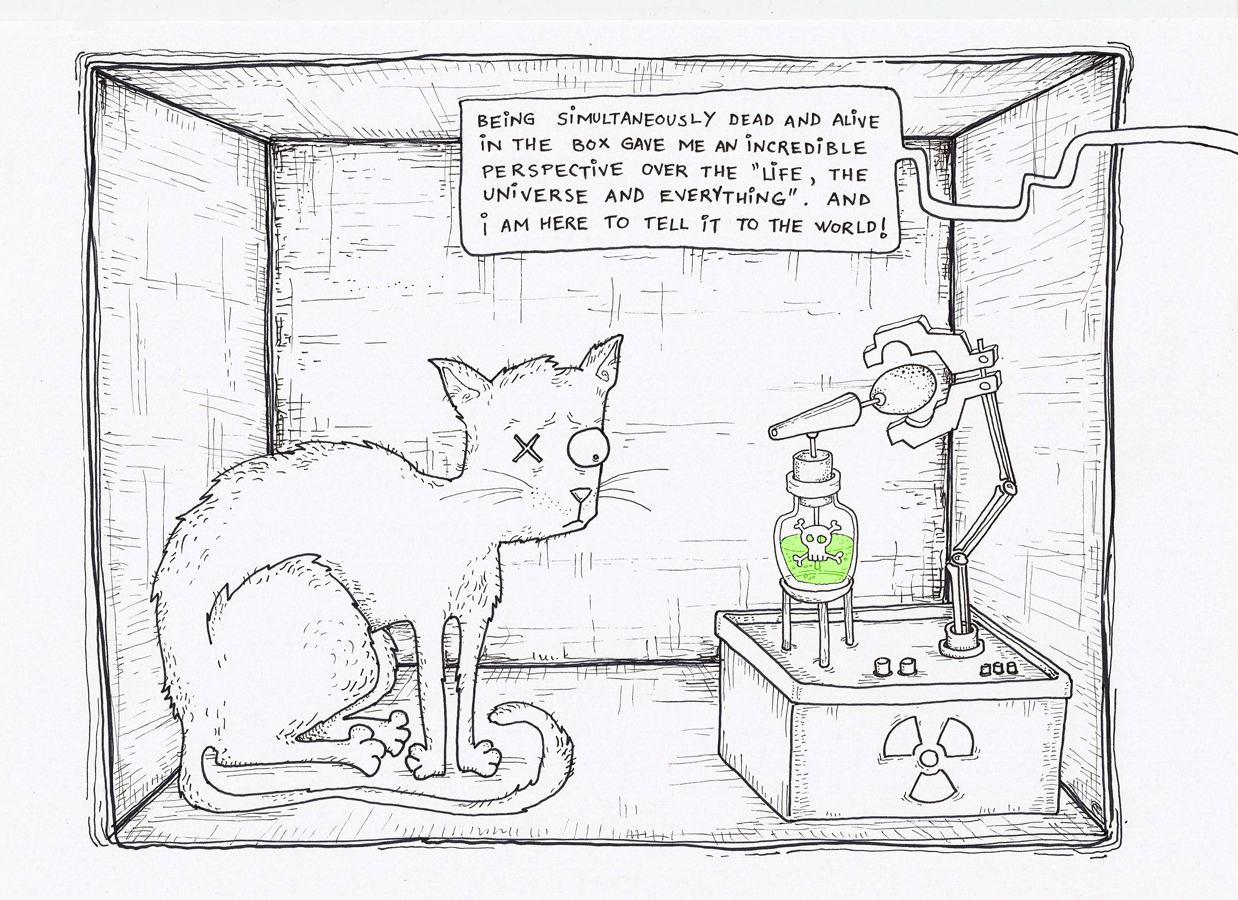

Recall that Hermitian operators have real eigenvalues. This explains why Hermitian operators are so central to quantum mechanics: the result of an experimental measurement must be a real number. The "chunkiness" inherent in quantum mechanics emerges from the fact one cannot observe an arbitrary value for the observable, but only the discrete eigenvalues of the corresponding quantum-mechanical operator. Ergo, Schrödinger's cat can be alive or dead, but not half-dead.

Hint: Use the Hermitian property of $\hat{Q}$ to evaluate $\int \left(\psi_k(x)\right)^* \hat{Q} \psi_k(x) dx$ in two different ways.

Denote the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of a Hermitian operator in the obvious way, $$ \hat{Q} \psi_k(x) = q_k \psi_k(x) $$

We call orthogonal and normalized functions orthonormal. A short-hand notation for orthonormality is: $$ \int \left(\psi_k(x)\right)^* \psi_l(x) dx = \delta_{kl} $$ where $$\delta_{kl} = \begin{cases} 1 & k = l\\ 0 & k \ne l \end{cases} $$ denotes the Kronecker delta symbol. The Kronecker delta symbol is the analogue of the identity matrix (extended to infinite dimensions).

Hint: Use the Hermitian property of $\hat{Q}$ to evaluate $\int \left(\psi_k(x)\right)^* \hat{Q} \psi_l(x) dx$ in two different ways.

When we expand a wavefunction in the eigenfunctions of a Hermitian operator, we say it is a superposition of the eigenstates of that operator. $$ \Psi(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{k=\infty} c_k \psi_k(x) $$ Measuring that operator always produces one of the eigenvalues, and the eigenvalues occur in proportion to the square magnitude of their coefficient in the eigenvector expansion, $$ \text{probability of observing the eigenvalue }q_k = |c_k|^2 = c_k^* c_k $$ The expectation value of the operator is thus: $$ \left<Q \right> = \sum_{k=0}^{k=\infty} |c_k|^2 q_k = \int \left( \Psi(x) \right)^* \hat{Q} \Psi(x) dx $$

This formula for the expectation value only holds for normalized wavefunctions. When the wavefunction is not normalized, instead one must use: $$ \left<Q \right> = \frac{\sum_{k=0}^{k=\infty} |c_k|^2 q_k}{\sum_{k=0}^{k=\infty} |c_k|^2} = \frac{\int \left( \Psi(x) \right)^* \hat{Q} \Psi(x) dx}{\int \left( \Psi(x) \right)^* \Psi(x) dx} $$

Hint: expand the wavefunction in the eigenbasis, use the eigenvalue relation and the orthonormality of the eigenvectors.

Immediately after performing a measurement of $Q$ for the system defined by $\Psi(x)$, one knows definitively that the state of the system is described by $\Psi(x) = \psi_k(x)$, with eigenvalue $q_k$. This seems weird, as the wavefunction seems to have changed abruptly from $\Psi(x)$ to $\psi_k(x)$ because of the measurement. This would somehow imply that if the wavefunction for Schrödinger's cat were: $$ \Psi_{cat} = \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|\text{alive} \rangle + \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|\text{dead} \rangle $$ and you opened the box and observed that the cat was dead (so after you open the box, $\Psi_{cat} = |\text{dead} \rangle$), then you killed Schrödinger's cat. To mildly exaggerate, some physicists would have you believe that every dead animal was slaughtered by the person who first observes its corpse. (To diminish culpability, it must be said that it the cat in this example was only technically half-dead, so the observer was a halfway-cat-assassin.) Most modern interpretations of quantum mechanics tend to deny such culpability. The physicists alibi is to assert that assert that while the system was described, mathematically, by $\Psi(x)$ prior to the measurement, this does not that the system existed in the state $\Psi(x)$. Similarly, after the measurement the system is in a state mathematically described by $\psi_k(x)$. While it would be weird for observing a system to be able to change its state, it is not weird for an observation to change our mathematical description of a system. For example, before you observe Lake Wobegon, it is reasonable to assume that all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average. But were you to visit Lake Wobegon, then based on your observation you might have to change your model.

That said, you may find the aforementioned "Copenhagen interpretation" convenient. Before my mother visits my home, I always clean it thoroughly. Nonetheless, my thorough cleaning is not up to my mother's standards, and she's always scandalized to find dust-bunnies under the sofa. (Who moves the sofa to vacuum under it, just to put the sofa back the same place and obscure the now-clean carpet?) I always tell my mom that the dust-bunnies were not there until she observed them. Unfortunately, my mom taught quantum mechanics herself, and she tells me that the wavefunction was: $$ \Psi_{dust-bunnies} = \sqrt{.0001}|\text{clean} \rangle + \sqrt{.9999}|\text{dirty} \rangle $$ I guess my home is only .01% clean (up to my mother's standards, at least).

The sudden change in the wavefunction upon observation is called wavefunction collapse. While the reality of wavefunction collapse in a physical sense is irresolvable, it is the mathematical description of what happens in a quantum system, and gives rise to strange quantum effects. If you find such things interesting, you may be interested to know that the aphorism that "a watched pot never boils" is justifiable, quantum-mechanically.

While the Born postulate is usually presented separately, it is in fact a corollary of the fact that physical observables are represented by Hermitian operators. The Hermitian operator that represents a particle at position $x_0$ is $\delta(x-x_0)$, where the Dirac delta function is effectively defined by its so-called sifting property.

Sifting property of the Dirac Delta function: Let $f(x)$ be a bounded function. Then $$ \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f(x) \delta(x-x_0) dx = f(x_0) $$

Now according to the Hermitian postulate, the probability of observing the particle at position $x_0$ is given by $$ \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \left(\Psi(x)\right)^* \delta(x-x_0) \Psi(x) dx = \left|\Psi(x_0)\right|^2 $$ which is the Born postulate.

Note: The Kronecker delta function has a sifting property similar to the Dirac delta function, $$ \sum_j f_j \delta_{jk} = f_k $$ This can be deduced directly from the definition, since $\delta_{jk}$ is one when $j=k$, and zero otherwise.

At this stage, your hand may be starting to hurt from writing integrals and wavefunctions. This is the motivation for Dirac bra-ket notation. A rather thorough explanation of this notation is available in my pdf notes, so I am only presenting the elements here. The basic idea is that a wavefunction is written as a ket, $$ | \Psi \rangle = \Psi(x) $$ and its complex conjugate as a bra, $$ \langle \Phi | = \left(\Phi(x)\right)^* $$ The overlap between two wavefunctions, which as we shall see is very important when expanding a wavefunction as a linear combination of basis functions, is therefore: $$ \langle \Phi | \Psi \rangle = \int \left(\Phi(x)\right)^* \Psi(x) dx $$ Because a Hermitian operator could act either forward (towards the ket) $$ \langle \Phi |\hat{Q} \Psi \rangle = \int \left(\Phi(x)\right)^* \hat{Q} \Psi(x) dx $$ or backwards (towards the bra) $$ \langle\hat{Q} \Phi | \Psi \rangle = \int \left(\hat{Q} \Phi(x)\right)^* \Psi(x) dx $$ we often use a notation that makes it clear that the operator can act in either direction, $$ \langle \Phi | \hat{Q} |\Psi \rangle = \int \left(\Phi(x)\right)^* \hat{Q} \Psi(x) dx $$

A set of functions, $\{\phi_k(x) \}$ is said to be a complete basis set if any wavefunction can be written exactly as a linear combination of these basis functions, $$ \Psi(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k \phi_k(x) $$ It is convenient and it is always possible, but it is not required, to choose the basis functions so that they are orthonormal, $$ \int \left(\phi_j(x) \right)^* \phi_k(x) dx = \delta_{jk} $$ where we have used the Kronecker-delta notation we introduced above.

In bra-ket notation, the preceding equations are, respectively, $$ |{\Psi}\rangle = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k |\phi_k\rangle $$ and $$ \langle \phi_j | \phi_k \rangle = \delta_{jk} $$

To obtain an equation for the expansion coefficient, multiply both sides of the first equation by $(\phi_j(x))^*$ and integrate over $x$. This gives: $$ \int \left( \phi_j(x) \right)^* \Psi(x) dx = \int \left( \phi_j(x) \right)^* \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k \phi_k(x) dx $$ Because the integral of a sum is the sum of the integrals, and because the integral of a constant is a constant times the integral, this simplifies to: $$ \begin{align} \int \left( \phi_j(x) \right)^* \Psi(x) dx &=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k \left[ \int \left( \phi_j(x) \right)^* \phi_k(x) dx \right] \\ &=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k \delta_{jk} \end{align} $$ Then from the sifting property of the Dirac delta function, $$ c_j = \int \left( \phi_j(x) \right)^* \Psi(x) dx $$ This is the equation for the expansion coefficient of a wavefunction in an orthonormal basis.

We have already alluded to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which states that some quantum-mechanical properties cannot be observed simultaneously. To provide a mathematical description of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, we need to define what it means for operators to commute and anticommute.

Two operators, $\hat{A}$ and $\hat{B}$, are said to commute if for any wavefunction $\Psi(x)$, $$0 = \left(\hat{A} \hat{B} - \hat{B}\hat{A}\right) \Psi(x) = \left[\hat{A}, \hat{B} \right] \Psi(x) $$ Similarly, two operators are said to anticommute if $$0 = \left(\hat{A} \hat{B} + \hat{B}\hat{A}\right) \Psi(x) = \left\{\hat{A}, \hat{B} \right\} \Psi(x) $$ In the right-most equality, we have introduce the standard notation for commuting and anticommuting operators.

In classical mechanics, observables are simply functions of the momenta and positions of the system's particles, and the since the momenta and positions commute, observables commute. However, in quantum mechanics, the momentum operator, $\hat{p} = -i \hbar \tfrac{d}{dx}$ is a differential operator, and does not commute with the position operator $x$. Because of this, measuring a particle's position first, then its momentum is different from measuring its momentum first, then its position. Conceptually, then, it is not unreasonable that if you try to measure the position and the momentum simultaneously, the system is "confused" about how it should behave (as if momentum were measured first? or as if position were measured first?) and the answer is uncertain.

If two operators, $\hat{A}$ and $\hat{B}$, commute, $\left[\hat{A}, \hat{B}, \right] = 0$. then one can simultaneously measure the corresponding properties $A$ and $B$. $A$ and $B$ are said to be simultaneous observables.

If two operators, $\hat{A}$ and $\hat{B}$, do not commute, $\left[\hat{A}, \hat{B}, \right] \ne 0$. then one cannot simultaneously measure the corresponding properties $A$ and $B$. A Heisenberg Uncertainty Relation then holds: $$ \sigma_A^2 \sigma_B^2 \ge \tfrac{1}{4} \left| \langle \Psi |[\hat{A},\hat{B}]| \Psi \rangle \right|^2 $$ where the variance in the expectation value of the operator is defined as: $$ \sigma_A^2 = \langle \Psi |\hat{A}^2| \Psi \rangle - \langle \Psi |\hat{A}| \Psi \rangle^2 $$

This expression can be made somewhat more precise by using the Schrödinger Uncertainty Principle $$ \sigma_A^2 \sigma_B^2 \ge \left| \tfrac{1}{2}\langle \Psi |{\hat{A},\hat{B}}| \Psi \rangle

A detailed derivation of these uncertainty principles is provided as a pdf.

Quantum-Mechanical Variational Principle): Given a wavefunction $\Psi(x)$ and a bounded Hermitian operator $\hat{Q}$, the expectation value of $Q$ is no less than the lowest eigenvalue of $\hat{Q}$ and no greater than the largest eigenvalue.

To understand where this principle comes from, let's focus on the lowest eigenvalue of $\hat{Q}$. We denote the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of $\hat{Q}$ as $$ \hat{Q} | \psi_k \rangle = q_k | \psi_k \rangle $$ and choose to list the eigenvalues are listed in increasing order, $q_0 < q_1 < \cdots $. Expand the wavefunction in the eigenvectors of $\hat{Q}$, $$ | Psi \rangle = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k | \psi_k \rangle $$ The expectation value of $\Psi$, which we assume to be normalized, is: \begin{align} \langle \Psi |\hat{Q}|\Psi \rangle &= \langle \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} c_j \psi_j |\hat{Q}|\sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_k \psi_k \rangle \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_j c_k \langle \psi_j |\hat{Q}|\psi_k \rangle \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_j c_k \langle \psi_j |\hat{Q}\psi_k \rangle \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_j c_k \langle \psi_j |q_k\psi_k \rangle \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_j c_k q_k \langle \psi_j |\psi_k \rangle \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} c_j c_k q_k \delta_{jk} \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 q_j \end{align} In the last line we used the sifting property of the Kronecker delta function. To complete the demonstration, recall that because the eigenvalues are listed in nondecreasing order, $q_j - q_0 \ge 0$ for all $j$. So: \begin{align} \langle \Psi |\hat{Q}|\Psi \rangle &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 q_j \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 \left(q_0 + (q_j - q_0)\right) \\ &= \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 q_0 + \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 (q_j - q_0) \\ &= q_0 \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 + \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 (q_j - q_0) \\ &= q_0 + \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |c_j|^2 (q_j - q_0) \\ &\ge q_0 \end{align} In the next to last line the normalization of the wavefunction, which implies that $\sum |c_j|^2 = 1$, was used. In the last line a nonnegative term was eliminated from the expression, resulting in the desired inequality.

This principle is especially useful for the energy, because it means that an approximate wavefunction will always have an energy greater than or equal to the true ground state energy. Therefore, if one is given two wavefunctions $\Psi(x)$ and $\Phi(x)$, the "better" ground-state wavefunction would be the one that has the lower energy. Similarly, given a normalized wavefunction that depends on a parameter, $\kappa$, the "best" wavefunction and the "best" energy can be obtained by minimizing the expectation value of the energy with respect to $\kappa$: $$ \min_\kappa \langle \Psi(\kappa) |\hat{H} | \Psi(\kappa) \rangle $$

The variational principle is one of the most important ways we approximate the energy and wavefunction of quantum systems.

Based on the preceding, the key postulates of quantum mechanics are

My favorite sources for this material are:

There are also some excellent wikipedia articles: